Additions and Subtractions

Finger

This morning I looked at two little scars on the palm of my hand from two surgeries I’d had for “trigger finger release.” The surgeries freed a pulley that was blocking movement, and after the surgeries the flexor could glide more easily through the tendon’s sheath. “Trigger finger” is a minor complication of my type-1 diabetes, but before each operation, as I was feeling drowsy from the anesthetic, I felt a sudden panic. What if the surgeon bungles it and I wind up with a dud finger? Or more than one.

I had a cousin, Robin, who lost a toe in a lawnmower accident when he was a kid. I always wondered how Robin felt when he changed his socks and how the missing toe affected his life ever after. I never asked him, although I became more cautious around manual lawnmowers. Robin became a poet and in his twenties emigrated to New Zealand. My mother read one of his poems and described what it was about. Could it possibly connect to the missing toe? According to my mother, in the poem a man is in his garden. He notices bottle of weed-killer on a shelf in the garden shed, and without really thinking about it unscrews the cap, drinks the weed killer, and dies an agonizing death. If you laughed at this, as my mother and I did, you understand something about English humor.

Dream

This morning, when I woke out of a dream, I was taking an exam about how to look after my diabetes. I didn’t understand the questions or the multiple choice answers for them, and it made me felt hopeless. This feeling has resonated with me all day.

I think my life

I think my life is always dealing with type-1 diabetes. I think my life has always required that someone say to me, “I love you.” I think my life is the same as other people’s lives because I don’t like other drivers or traveling by plane, and I sometimes forget to turn off my phone. I think my life is distorted by Facebook because the things I write on Facebook distort my life. I know my life would be better if I knew how to play the piano.

Cure

When I hear about “cures” for diabetes, I call them “Tales from the Islets of Langerhans.” The islets—named after the German pathologist Paul Langerhans, who discovered them in 1869—are cells in the pancreas that secrete insulin (as beta cells), among other hormones. You’ve got a chronic condition, people want you to be rid of it. Sure. But then they tell you about Peter’s cousin Lou, who started eating a root, or drank a mess of herbs, or began practicing this form of yoga, and boom, he was cured. Don’t you want to try it? No thank you.

Diagnosis

Leeds in 1973—despite housing the country’s largest urban university—remains for the most part working-class grim. The cab I’m in speeds through labyrinthine streets of back-to-back terraced housing. Washing flaps on lines strung across side streets. Neighbors chat to each other from door steps. Pubs are the main life of the community, and there is one on every other street, interspersed by fish-and-chips shops and corner stores that sell sundries, among them single fags for those who can’t afford a pack. Here and there soot-blackened churches are becoming Sikh temples and Muslim mosques.

I’m driven in a taxi on instructions from the university’s student medical center. A routine urine test has shown high levels of glucose. At the hospital, I’m given a bed on a ward with five other men. One, a hemophiliac about my age and from a village like the one where I grew up, paces the corridors until he’s informed he needs an operation. Urgently. He’s told his chances of surviving are fifty-fifty. Everyone overhears this. It’s horrifying, and I’m stunned by his reaction, which is no reaction at all. He says okay, his eyes cast down, his chest curving inward. I want to say: “Speak up for yourself. Ask questions. Are there other hospitals that specialize in your condition? Do you need a second opinion? What is the track record of the surgeons on your case?” I say nothing, wondering what I would really say in his place. Am I in his place?

In another bed, a bus driver in his fifties is recovering from a heart attack. He’s so frustrated by the late arrival of his meal he smashes a plastic plane he’s spent the day gluing together. I want to smash something too. It’s evening, and I still don’t know why I’m here. Kay arrives with my overnight things and demands answers from the nurses, who are tight-lipped. “Wait until doctors’ rounds,” they say. It’s Friday evening, and no one is planning to arrive until rounds on Monday morning.

It’s Saturday night when an orderly asks me to pee into a bed pan. Under his impatient eyes, I manage a trickle. I’m handing over the pee when I notice, written along the side of the container: “Richard Toon—diabetic.” I say, “Does this mean I’m diabetic?” He says, “Yes,” and strides away.

Sugar times

I’m alone one night watching Field of Dreams on TV. As my blood sugar drifts down, the movie becomes more and more profound. Death isn’t the end! We’re too bounded by reason to catch the shafts of light all around us! I look up from the screen and see the living room through a fish-eye lens. The bookcase is swaying. The arm chair is mumbling quietly to itself. My hands are attached to extremely long, rubbery strips, and the hairs on my arms, light brown and silky, are beautiful and mysteriously meaningful. A drop of sweat runs down my forehead, splashes onto my thigh, and ripples like a droplet on the surface of a pool. And I think—very slowly and with a smug smile that signals danger—I’m having a really low blood sugar.

I find myself in front of the refrigerator with the door open. Cold air moves across my skin. I’m slick with sweat, just sweating all over, and I can’t remember what I’m supposed to eat. I bite off some cheese (bad idea, it has no effect on blood sugar), and I grab a container of orange juice and gulp it (good idea, sugar galore). Ten minutes later, I feel normal again and watch Kevin Costner meet his dead father in a cornfield. He’s stiff, and James Earl Jones is a blubbery fool encountering dead baseball players. I, too, feel wooden and spent, ejected from my field of dreams.

In one rather precariously low sugar, while Suzanne, my wife at the time, was handing me a glass of orange juice and waiting for my jumbled speech to mean something, I was convinced that time was running backwards. I could swear that everything had already taken place—a sustained sense of deja-vu. I said, “I've just drunk the OJ” and “How come time is going in reverse?" If you've seen the film Memento you'll remember that the main character goes around without any operating memory and has to piece together what’s happened to him from notes he leaves on his body. As he constructs and reconstructs this knowledge, the story is revealed to him (and us) in reverse. My experience felt like this, and the odd sense that it engendered—that you feel ahead of the game, hence the oily smile—stayed with me for days.

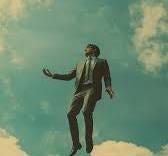

I understand these moments are tricks of blood sugars, but I see them, nonetheless, as special mental abilities. I'm not saying time was really running backwards, rather I enjoyed the sights and sounds as you might a journey to the Arctic or the Amazon, even though you would not always want to live in these extremes. How many Richards am I? In the rhythm of sudden sickness and rapid recovery, I experience little deaths and rebirths many times, even in one day. The return to a sense of self, not shaken in the fist of either a high or low sugar, is sweet in the same measure as altered brain states are illuminating. I feel hopeful as I reassemble the fractured parts of me, languid on a couch, the littlest hairs on my body feeling air moving on them. I am small and excited, ready to evade repetition.

There are three links at the bottom of my post: “like,” “comment,” and “share.” Please engage with my stack so the algorithm will get to know me. I also would love to hear your comments about the posts.

I love all the bits woven in here and how the altered states are illuminating.

So intrigued by all intense and fluctuating selves. I felt I was following you into them.