I was with K when I was first diagnosed. She wasn’t at all down-hearted by the news and in her company neither was I. It was better than that. I found myself swept up into her enthusiasm for getting things right. She took to diabetes with as much gusto as she took to new areas of knowledge.

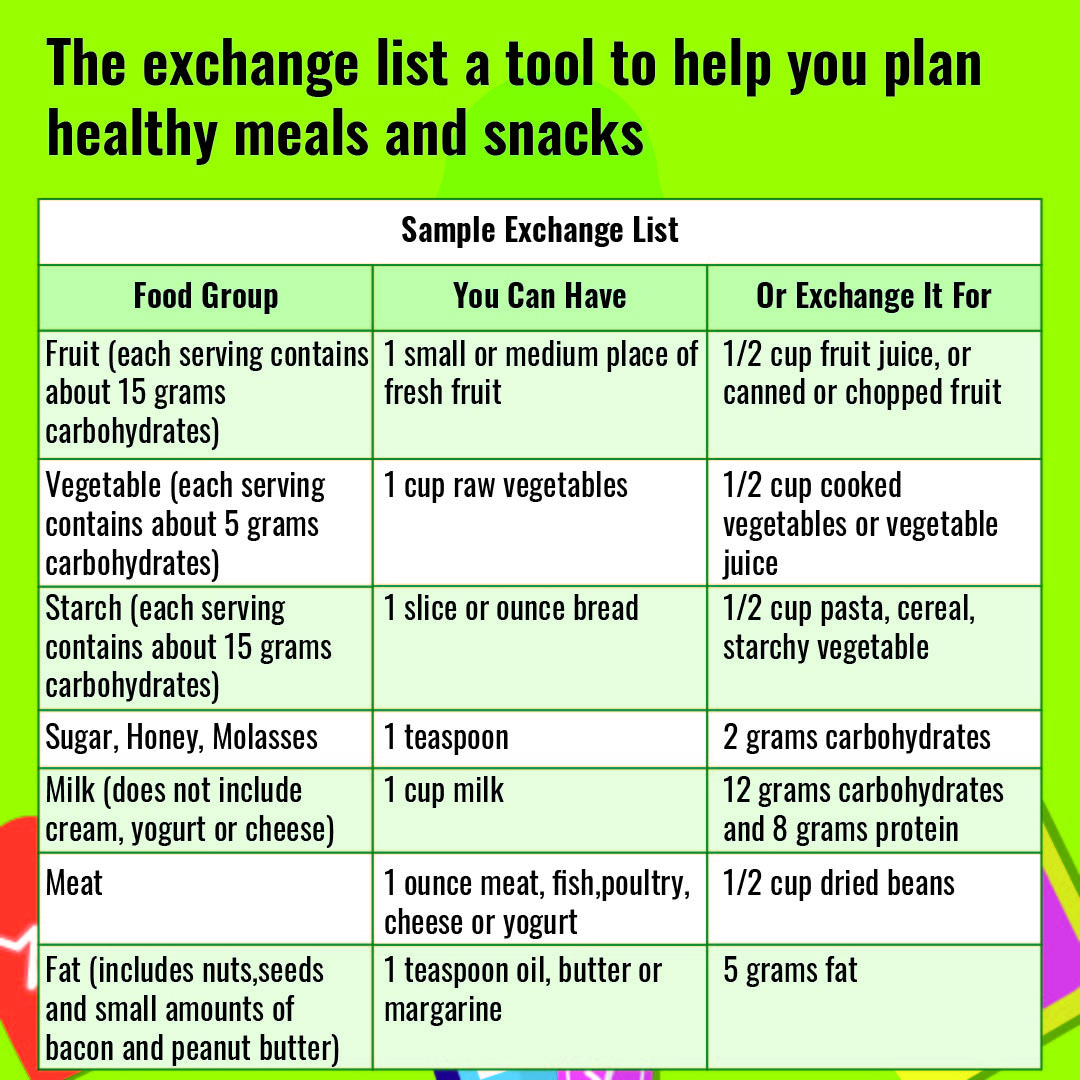

She discovered the “exchange system” of foods for diabetics, using it to work out my daily requirements of starches, fruits, vegetables, dairy products, meats, etc. She would sit at the kitchen table, weighing different foods on a small plastic scale, and she’d consult long lists of exchange values. From these she developed weekly meal plans and announced we would both be eating according to the system from then on. And so we did, until K drifted to other enthusiasms and the strict calculations and dedication was itself exchanged for quick assessments of how much of this or that to put on a plate.

The pattern with food—of interest followed by waning interest—was pretty much the pattern people fell into with the disease itself. At first it was very much on the minds of everyone we knew. Friends and acquaintances either visited during my weeks in hospital or sent not-really-relevant “get-well” messages. My parents telephoned often and showed great concern in a non-specific way that’s understandable, since I didn’t seem sick. I found myself consigned to that archipelago of their regard I call “poor old X”—a place set aside for people they felt sorry for but didn’t actively help, among them our aging relatives, “poor old Olive” and “poor old Bill.” My mother started ending each call to me with, “Ah, poor old Rich. I’ll call you in a few days.”

An article I read recently suggested three terms for phases people pass through when they get a disease: "interruption, intrusion, and immersion.” These are useful terms, and I can see what the writer meant, but I think my phases were: “welcome, overwhelmed, and identity.”

When I was first diagnosed, it was certainly an interruption, but it was also like receiving a new guest. Maybe you don’t know quite where to put them, but they’re not necessarily an intrusion or unwelcome. In my case, I felt more a sense of interest and intrigue than interruption. Once I learned the name of my new guest, there was something enjoyable about becoming acquainted.

I was also relieved to know why I was so tired in the afternoons and had trouble concentrating. My friend Neil, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, was similarly delighted to understand his moods. He rushed out, as I did, to become a student of his condition. I can remember enjoying the learning curve, while family and friends were seeing only the down side.

In the second phase, the intrigue begins to pall and your “interruption” is well on the way to being an “intrusion.” The condition now looks like something that has crashed into your life and is making daily and monotonous demands. You try to make friends with your companion, diabetes. You go along with what it wants. Is it grateful? No. It refuses to leave and becomes even more demanding. You want to ignore it, but that's dangerous, because to do that will make you really ill. All out war is impossible because you will always lose. Eventually you acknowledge a third and final option: you are the condition.

The other day I read advice from a diabetic educator who counseled not to refer to people as “diabetic” but rather as “a person with diabetes.” The movement in this thinking has mainly been around conditions you don’t recover from, so “person with autism” rather than “autistic,” and “person with schizophrenia” rather than “schizophrenic.” It’s meant to reduce the stigma of seeing the person as their condition—as if they are a walking, allegorical incarnation of an abstraction.

I’m fine with that. In fact, I like it. It’s helped me. I think some fiddling with language as a form of sensitivity policing can be dishonest and rupturing to at least my sense of self. The beta cells in my pancreas don’t produce insulin, therefore I am.

After 50 plus years with diabetes, I don’t yet have any of the complications that kill you—among them strokes, heart attacks, kidney failure, etc. I don’t find anything to be proud of in this. I’ve taken care of myself, and I’m probably genetically lucky (if you don’t count the genetic factor in developing type-1 in the first place, which is an auto-immune disease triggered by, possibly, a temporary viral illness.) I loath heroic “life with diabetes stories,” where someone conquerors the north face of the Eiger in a blizzard or heads the Olympic badminton team, all the while calibrating their insulin pump.

To me, these stories read as survivor literature, which on one hand say you can do anything with diabetes and on the other hand suggest you have to be pretty damn special to do so. I understand that many people with bone cancer and breast cancer, for example, find it necessary and useful to others to write about how they beat it. That’s because they have a disease that’s treatable and is not necessarily who they are. The brute fact I live with is you don’t survive diabetes. You don’t go into remission. To date, it’s an irreversible, chronic disease, which means you die with it. If you’re lucky, perhaps you don’t die of it.

It used to depress me when I’d read in the news that so-and-so died of the complications of diabetes. I think the last person I remember reading that about was BB King. I think I found it a kind of failure—precisely the kind of failure survival literature implies if you aren’t a hero who’s evaded death. Survival literature, however valid and soothing for some people, embraces a full-blown Cartesian dualism. My inclination is toward an Aristotelian body-soul identity.

I am my body. A small change in my blood sugar appears to determine my mind’s understanding and my experience of aliveness. I won’t look for heroic stories or feature in any. I’ll simply complain chronically to the grave that is oblivion. I expect, in surviving, to conquer nothing. My job is the reverse: to learn to live with me.

______________________________________________

Welcome to new readers and subscribers!

This is post number five. I’ve had a good start, it feels, and I’m very grateful to everyone who’s supporting my new Substack, EVERY TWENTY MINUTES. In each post, I will be writing through the experience of chronic illness and type-1 diabetes, although not always directly about these topics. I may be more than one person, but all of them have my condition.

There are three links at the bottom of my post: “like,” “comment,” and “share.” Please engage with my stack so the algorithm will get to know me. I also would love to hear your comments about the posts.

I expect, in surviving, to conquer nothing. My job is the reverse: to learn to live with me.

Brilliant!

Another terrific post!