When I came to, the engine was still running. I must have driven off the road into a drainage ditch. It was dark. The rhythmic red flashes of a police vehicle illuminated the street. Where was I, and how did I get here? A police officer opened my door and asked me what happened. I said I didn’t know. I said I was driving home. He asked me how I was feeling. It was hard to concentrate. He asked for my wallet. I may have passed out again. When I woke up, there was a fire truck with a different rhythm of flashing lights. I drifted in and out of consciousness. I don’t know how I revived. I don’t remember how I got home or what happened to my car. Perhaps someone injected me with glucagon to raise my blood sugar.

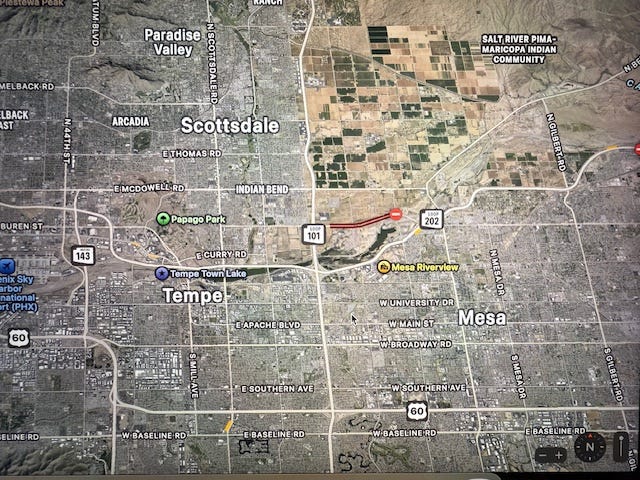

In time, my head cleared enough to realize I must have turned off the highway onto the reservation—the land of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. The cop was from the tribal police. I remember seeing the badge on his shirt. The reservation ran along the 101-loop highway, connecting Tempe to Scottsdale. The cop said they’d received a call saying someone was driving drunk, swerving back and forth along the road. He said, “I know you’re not drunk.” In the glow of the flashing lights, I could see I’d driven into a road sign that leaned over the front of the car. The cop said it saved me from going further into the ditch. He said I might have to pay for a new one. He said, “I won’t cite you, feel better, I hope you’re okay.” I was never asked to pay for a new sign.

Earlier, I’d been driving home along the 101, and I remember thinking my blood sugar was dropping. I remember thinking, it’s just another five or ten minutes, I can make it to the house. I’d been teaching an evening class that ended around 9 pm. A student had asked me a question about museums. I remember talking for a few minutes and then walking across the campus with the student.

I don’t remember who it was or what we talked about. I remember walking up three flights of stairs to my car. Walking up stairs doesn’t help when your sugar is dropping. The stairs overlooked the pool where the Arizona State swimming team practiced. Michael Phelps had recently joined, and I looked over to see if I could catch him. The rest is a series of broken images, ending at the drainage ditch. It’s been quite a few years since this happened. I’m not sure whether the gaps in my memory are due to time passing or trying to remember something when my memory at the time was already shredding. I’m thinking it’s both.

The medical term for short-term loss of consciousness is “syncope,” from a Greek word for cutting-off, cutting-up, or cutting-short. I’m not sure how brief it was in my case, because, in an important sense, I wasn’t there. Does that mean I’m still responsible for the accident?

The cop didn’t cite me for anything, but I’m pretty sure he would have had I been drunk. The ancient Greeks thought about drunks. They thought deciding to get drunk in the first place made you accountable for anything that happened afterward. With diabetes, the issue of accountability is complicated because one consequence of a low sugar is you deny you are having one, and you deny the need to correct it. Laurie has told me many times my denial, when I’m in a low, ramps up as I’m getting lower.

In law, the test of responsibility is usually, “What would a rational person do?” So, what level of responsibility does one have once rationality isn’t available, due to too much insulin? If, during the class, or later, talking to the student, I’d chewed some glucose tablets, probably none of this would have happened. Am I responsible for not taking the tablets, even though, during the time to take them, I’m already in denial I need them? You can see it’s a catch 22.

Dr. Elliot Joslin, the pioneer of diabetes treatment, proved that tighter control of glucose levels led to fewer complications and less extreme forms of them. His biographer wrote that Joslin encouraged his patients to have “. . . a strong Protestant work ethic, a zealous attention to detail, and high regard for self control.” This amounts to requiring a moral ethic in tandem with a diagnosis of type-1. It’s why I was expected to think about my diabetes “every 20 minutes.” In the past, how did you know you were an upstanding citizen of your disease? Your success was measured via the A1C test that became available in the early 1980s. It showed the average blood sugar level over the past 2 to 3 months. The higher number, the poorer the control.

Over the years, I’ve become friends with both type-1 and type-2 diabetics. At some point, the competitive nature of diabetic control, as shown by A1C test results, always comes up. I wonder if this is true of people with other chronic conditions. Do they get to compare results, or are you on your own? Maybe it’s human nature to want to get an A on every test. Maybe there’s no such thing as human nature. Maybe every test taker is alone.

These days, I off-load much of the record-keeping of tight control onto the extended minds of my insulin pump, sensor, and phone app. When I visit my endocrinologist, we review the down-loaded data and run a variety of reports. It’s similar to going over a student’s essay and saying where they have done well and what needs further work. It’s not as potentially morally pressuring as in the past. The technologies make the doctor-patient relationship more collegial than in Joslin’s day. No one can be expected to fulfill the demands of regulation all the time. Still, I always feel inadequate. I could do better with my tests and awareness of lows and highs! Perhaps tomorrow.

________________________________________________

Welcome to new readers and subscribers!

This is post number seven. I’ve had a good start, it feels, and I’m very grateful to everyone who’s supporting my new Substack, EVERY TWENTY MINUTES. In each post, I will be writing through the experience of chronic illness and type-1 diabetes, although not always directly about these topics. I may be more than one person, but all of them have my condition.

There are three links at the bottom of my post: “like,” “comment,” and “share.” Please engage with my stack so the algorithm will get to know me. I also would love to hear your comments about the posts.

Hey Richard, great post. It made me think about responsibility while living with a chronic disease. I liked your comparison with intoxication. Taking responsibility for our own health is many layered. I recently asked my PCP to prescribe a mood stabilizer for me again. I’d stopped it a couple of years ago after taking it for 20 years. Lately, I can’t seem to regulate my moods and had to admit the chemical imbalance in my brain needed some pharmaceutical help. I’ll have to live with the side effects.

i’m struck by the intuitive compassion of that highway patrol officer; how rare and lucky for you. i also marvel about how our bodies function; how sometimes our physiology works in our favor (vomiting, allergic reactions, eyes tearing up to cleanse debris) and then the opposite, as with low sugar, which creates the unhelpful side effect of obstinacy. if laurie can tell over the phone you’re in that small window right before you get there, is it because your voice starts to slur or slow down or you’re just not making sense?