I read medical articles. They are mainly results from the longterm study of diabetes I’ve volunteered for. It’s all useful background information, but it makes you hypochondriacal. It makes you think you have conditions you didn’t know about before you read the articles. I’m reminded of a passage in Three Men in a Boat (1889), in which the author, Jerome K Jerome, recounts an incident moment before setting off on a rowing trip along the Thames:

“I remember going to the British Museum one day to read up the treatment for some slight ailment of which I had a touch – hay fever, I fancy it was. I got down the book, and read all I came to read; and then, in an unthinking moment, I idly turned the leaves, and began to indolently study diseases, generally. I forget which was the first distemper I plunged into – some fearful, devastating scourge, I know – and, before I had glanced half down the list of ‘premonitory symptoms’, it was borne in upon me that I had fairly got it.

“I sat for a while frozen with horror; and then, in the listlessness of despair, I again turned over the pages. I came to typhoid fever – read the symptoms discovered that I had typhoid fever, must have had it for months without knowing it –wondered what else I had got; turned up St Vitus’s Dance – found, as I expected, that I had that too – began to get interested in my case, and determined to sift it to the bottom, and so started alphabetically – read up ague, and learnt that I was sickening for it, and that the acute stage would commence in about another fortnight. Bright’s disease, I was relieved to find, I had only in a modified form, and, so far as that was concerned, I might live for years. Cholera I had, with severe complications, and diphtheria I seemed to have been born with. I plodded conscientiously through the twenty-six letters, and the only malady I could conclude I had not got was housemaid’s knee.”

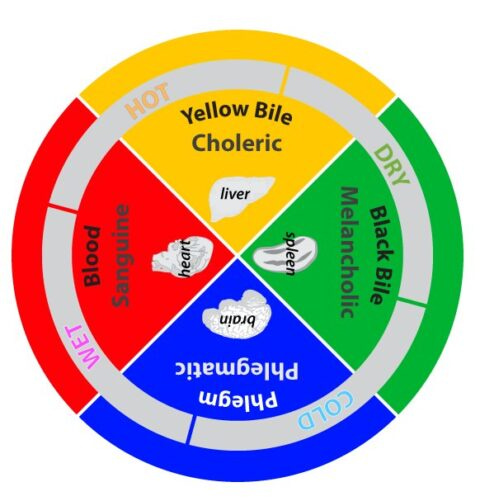

The hypochondriac is a person who imagines they have an illness they don’t have. The root of the term in ancient Greek refers to the hypochondrium, that is, the area under the ribs containing the liver, the gallbladder, and the spleen. I think the pancreas is nearby. Don’t make me look. The Greeks believed this area of the body was the source of melancholy, the mood disorder that included sadness, anxiety, and depression.

I have found you can’t have diabetes long without feeling some melancholia, which is also a Greek term for “black bile,” supposedly secreted by the spleen. The Greeks believed that feelings and emotions were not only a brain state but were also situated in some other parts of the body. I’m with the Greeks and the later scholastics on this, maybe we need to rethink the notions of the four humors. Not so fast, I don’t think this theory would have led to the insulin pump and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM).

I don’t know if there’s a term for the sympathetic attachment people can come to feel when partnered with a mate’s chronic illness. I’m thinking here of Laurie and the other women I’ve lived with after being diagnosed, in 1973, with type-1 diabetes. Fellow chronic isn’t quite right, but it’s in the ballpark. Perhaps we need a neologism based on Greek terms, combining sympathy, coping, and intervention.

My various partners have formed quite different relationships with me and my condition. This is understandable, given that each has reacted to an illness with radically changing treatments along the way and each had their own relationship to illness.

I was with K in the ‘70s, when the illness began. At that time, there wasn’t the roller-coaster of highs and lows that came with trying to keep blood sugars as low as possible. It was more getting around, without collapsing or dying or feeling sick from a high, but you lived in a general fog that never cleared. K and I enjoyed weighing food and calculating values from lists of “food exchanges.” People enjoy what there is to enjoy when they are in love.

I was with N a decade later, when, in 1984, I joined the DCCT study. She had read in a magazine that researchers at New York Hospital were recruiting volunteers for a study. I matched the profile for subjects, and she urged me to join. I remember N talking about “living with the sick body” and the concerns that were always breaking into the rhythms of our life together. I could understand this from her perspective. From mine, there is only me in the body I have, and whatever defines that body is also me.

Laurie took over the partner role in 2006 and found more than one me. Recently, I prompted her to convey what riding in the side-car of an illness feels like, and this is what she wrote:

“Richard is thinking about the fact he can’t know what he’s like and can’t remember what he says and does in extremely low blood sugars. They are altered brain states similar to drug trips or alcoholic blackouts, where memory is erased.

“He doesn’t know that guy, who sometimes doesn’t know the meaning of the words he’s saying. That guy sometimes can’t speak. That guy is super strong and will push against you if you try to feed him things to raise his sugar levels. That guy is fearful something is happening to him he can’t control, and although he is sweating and babbling and his eyes are glazed, he will insist he’s not having a low sugar.

“. . . . Yesterday, we were walking on Warren Street, and I said, “I think that guy is the real you, and the other Richard you are most of the time is the impostor.” He said, “Really? You think I’m angry and violent?” I said, “No.”

“I was thinking of something Bryan Cranston said about playing Walter White in Breaking Bad, a high school chemistry teacher diagnosed with terminal cancer, and his alter ego Heisenberg, a meth kingpin who goes up against a Mexican drug cartel. Cranston said he played Walter as the impostor and Heisenberg as his true identity all along.

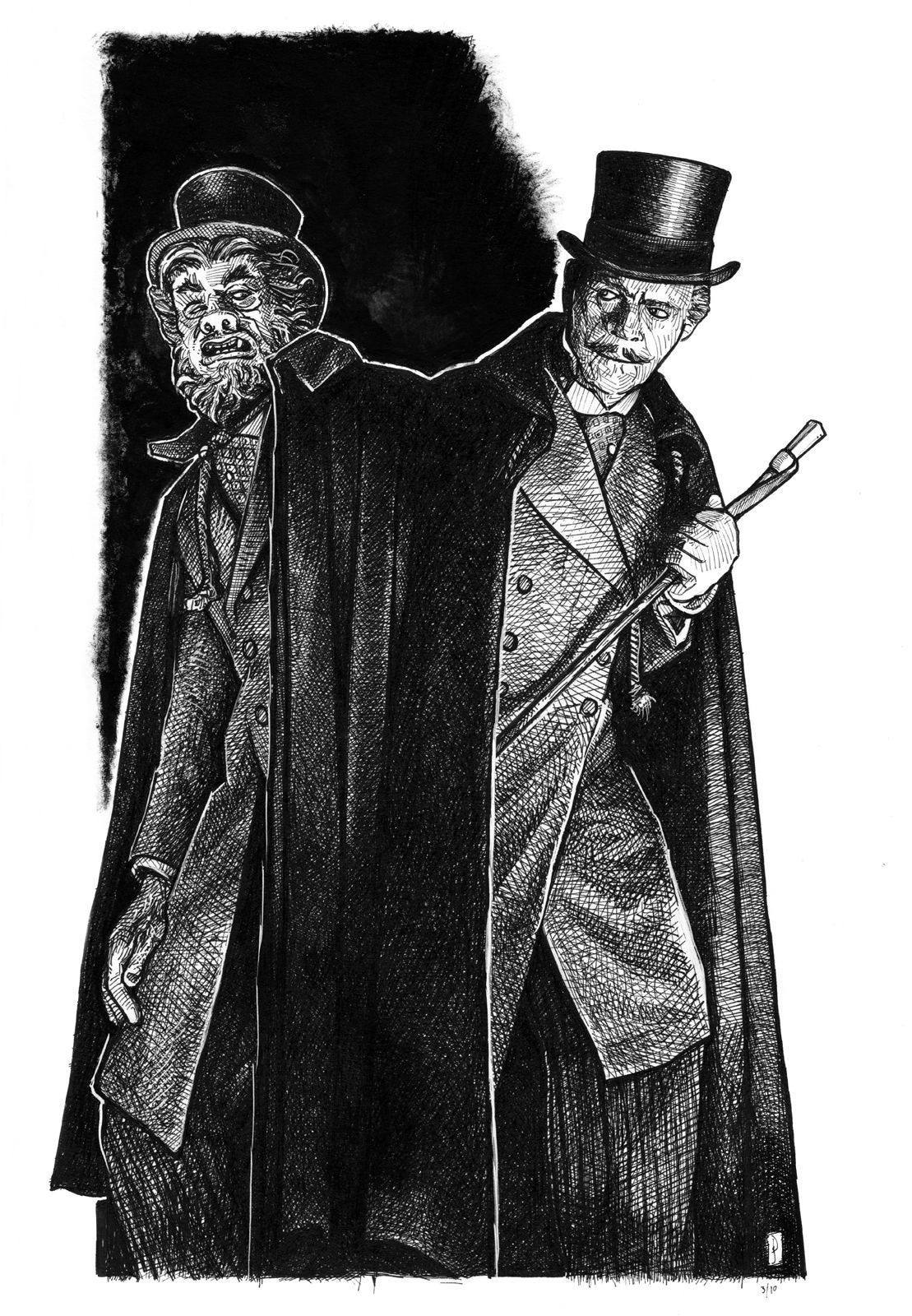

“I said the thing to Richard because it was funny. A “what if?” the charming and sensitive person who goes around with that adorable English accent and shy smile is an act, and the real Richard, as in the Jekyll and Hyde story, is only allowed out when the moon is full and blood is in his throat.

. . .

“When Richard asks what it’s like to live with a person with two different personalities, depending on the amount of glucose floating in his blood, I tell him it’s fine, most of the time. To me, most of the time, he is one person with fluctuating moods and abilities to function. I was hyper-alert when we met, and this has come in handy in our relationship. Maybe it’s the core saving factor in our relationship, not in a female nurse sense. More in the sense of someone is awake all the time, allowing the other person to sleep, like in The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, where, when you fall asleep, the pod people come and replace you with an empty replicant.

“The only time these dips really get in the way of my peace of mind is when Richard slips into one of those really low sugars. He doesn’t know it’s happened, and I didn’t see it coming because I wasn’t around. At those times, I become hysterical with an edge of futility that causes rage in me. This may seem odd. Why get angry at a person who can’t help himself? It’s stupid, but that’s my response to my own helplessness to bring him back. A year or so ago, when he fell into such a low low, I had to call an EMS crew to revive him with a glucose IV, there were a few seconds when he wasn’t responding to anything. He was lying on the floor, and I thought he might be dead.

“Soon, he stirred or made a sound, showing he wasn’t dead, but a panic and pain went through me that felt like I was dying. If Richard died, I would be dead, for all intents and purposes.

“I had found him in his studio, sitting in his chair, sweating. I knew he was having a low sugar, but by the time I was downstairs, he’d fallen so low he wasn’t able to chew glucose or drink or eat anything. I didn’t know that and tried to bring him back with the usual methods of glucose tablets, chocolate, and orange juice. I couldn’t understand why he wasn’t coming back and was slipping further away. It turned out, he wasn’t swallowing anything. His mouth was filled with gunk, and when he slowly returned to himself, he said, ‘What happened?’”

Laurie shows there is someone I become during bouts of low sugar I know little about. I don’t think there is a permanent self, but I’m not happy thinking there might be another me. If there is another me, it’s not one created by the condition itself. It’s a product of trying to maintain low blood sugars, taking too much insulin, and then, and only then, Mr. Hyde makes an appearance.

_______________________________________________

Welcome to new readers and subscribers!

This is post number four. I’ve had a good start, it feels, and I’m very grateful to everyone who’s supporting my new Substack, EVERY TWENTY MINUTES. In each post, I will be writing through the experience of chronic illness and type-1 diabetes, although not always directly about these topics. I may be more than one person, but all of them have my condition.

There are three links at the bottom of my post: “like,” “comment,” and “share.” Please engage with my stack so the algorithm will get to know me. I also would love to hear your comments about the posts.

Love and admire this, Richard. A great intertwining of things. And apropos of nothing, but speaking of intertwining, I realized that you could both take on the last name Toon-Stone.

“Bright’s disease, I was relieved to find, I had only in a modified form, and, so far as that was concerned, I might live for years.” So glad to hear this. 😜

Another delightful post, Richard.